They say you should never judge a book by its cover, but you should also never judge one by its title. When I first picked up Joanna Scott’s latest book, Careers for Women (Little, Brown and Company), I thought it would be a book about, well, careers and women. What I got was so much more: a story steeped in historical fiction enveloped by the power of friendship, love, determination, greed and murder. The book begins in the late 1950s, in which we meet Maggie Gleason, a staffer working for Lee K. Jaffe, the real, yet often forgotten, trailblazer and mastermind behind New York City’s World Trade Center who served as the director of public relations for the Port Authority from 1944-1965. Mrs. J, as she is fondly called by her staffers, serves as a mother figure to these women, who aspire to emulate her successful career as a female executive, and is even more to Pauline Moreau, a streetwalker with a young daughter who Mrs. J takes under her wing. The story spans several decades, following the pursuits of Maggie and Pauline – who become friends after Mrs. J asks Maggie to look out for Pauline – as they build lives and careers in an arena ruled by men. Meanwhile, an aluminum conglomerate in upstate New York is destroying the environment and land; though the business name may be fictional, the issue was very real. Scott expertly weaves together these two worlds, both of historical significance, producing a story that warns of the dangers of corporate greed and how a ball of lies can unravel, hurting, and even killing, those in its way.

In 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt published her first book, It’s Up to the Women, which was recently re-released by Nation Books. Roosevelt released this book at the height of the Great Depression as a guide for women of all ages on what they could do to keep the economy going in the trying and changing times that had befallen the United States. Roosevelt addresses a wide range of topics, such as marriage, finances, raising children, keeping a home and the importance of family values. At the time, the home was the woman’s domain, but the second half of her guidebook – in which Roosevelt discusses women in the workplace, in public/civic life and even the possibility of a female president someday – is what is truly revolutionary about her advice. According to Jill Lepore, who penned the 2017 release’s introduction, Roosevelt never wanted her husband to run for president; rather than surrender her independence, she decided to reinvent the role of the First Lady and became a champion for women’s and civil rights, including writing this book, which was published two months before her husband’s inauguration. It is fascinating to comb through Roosevelt’s thoughts more than eight decades later and realize that much of what she had hoped for, in regards to the mobilization of women in the workplace and in public life, is still relevant today.

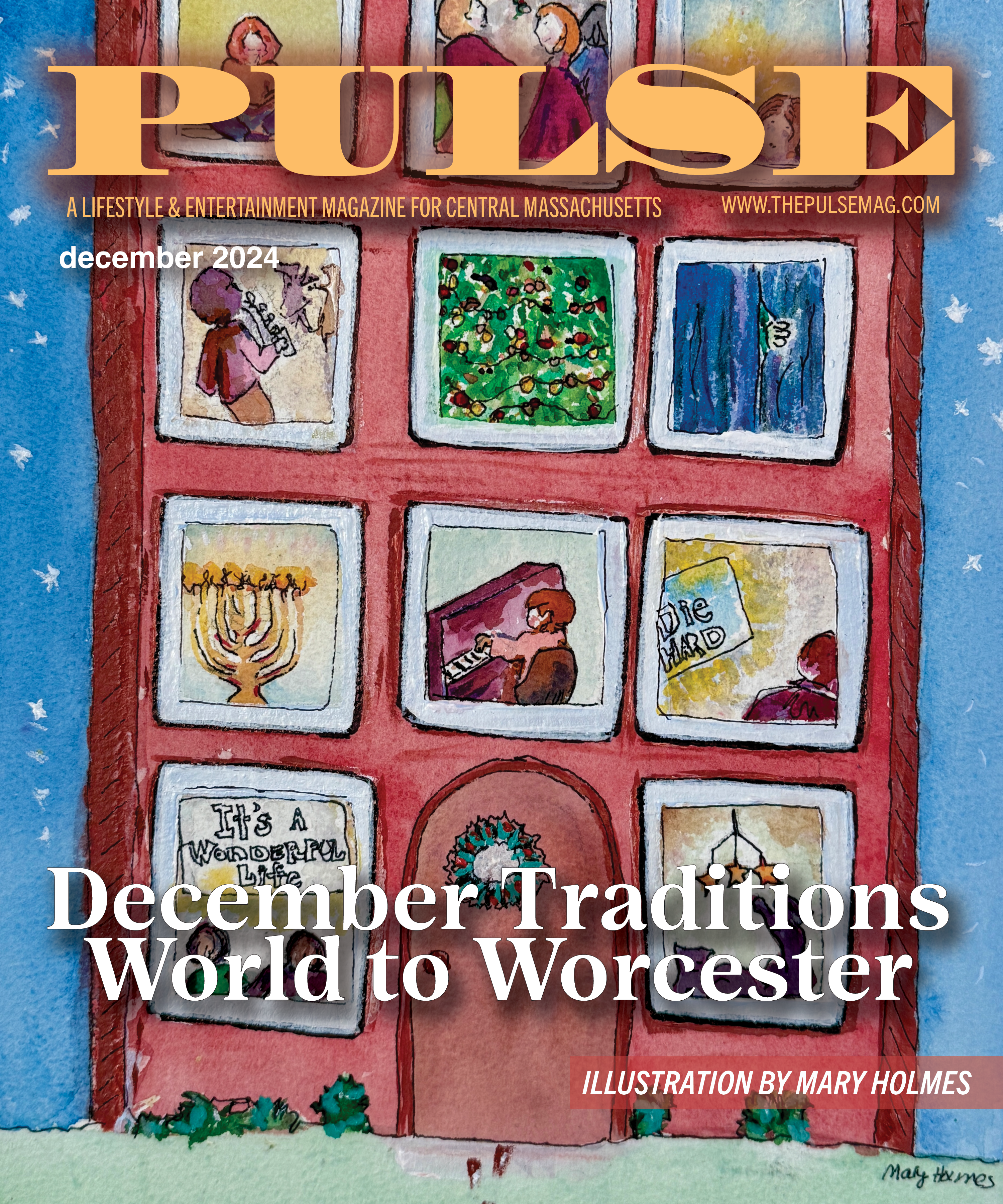

Kimberly Dunbar