On September 13 of this year, at approximately 6 p.m., Eastern Standard Time, Worcester’s Jose Rivera found himself in a boxing ring in Berlin, Germany, physically exhausted after 12 rounds of boxing and straining through the noise and confusion to hear if the ring announcer would say his name.

November 2003 – “I couldn’t understand what they were talking about,” he recalls. “I just kept waiting to hear my name. If I hear the name, then I know who won.”

Rivera felt that he had outfought his opponent, WBA world welterweight champion Michel Trabant of Germany; but he also knew that he was on enemy turf, and that strange things happen with regularity in the tumultuous world of professional boxing. He had been working 14 years for this moment, and it had all come down to the matter of a foreign announcer in a foreign land pronouncing his name.

“When they mentioned my name,” he recalls, “then it was an overwhelming feeling like, “Oh my goodness, I did it,” and I just dropped on my knees and thanked God, kind of like in unbelief.”

The German fight fans believed it, however, and they even booed the one judge who had scored the fight even. Rivera’s fans back in Worcester believed it, having suffered the agony of watching the fight on a one-frame-per-ten-seconds web cast. Who wouldn’t want to believe it? It confirmed the old fashioned notion that good things sometimes do happen to good people; that hard work pays off; and that nice guys sometimes do finish first.

Jose Antonio Rivera came to Worcester in 1990 — came here from Springfield, where he was living with an aunt and felt he was going nowhere. He came to Worcester because of Carlos Garcia, the fabled boxing coach at the Ionic Avenue Boys and Girls Club. Garcia had told him that he would work with him, which was enough of a promise to induce the 16-year-old to make the move to a strange city. Garcia also told him he had to finish high school as part of the bargain, and so Rivera took an apartment with fellow boxer Bobby Harris and diligently completed his studies at South High School.

It was the “sweet science” of boxing that attracted him, however, and it was that curriculum that he pursued with dedication in the bowels of the city’s aging Ionic Avenue clubhouse — day after day, season after season, pounding the heavy bag, rattling the speedbag, and swinging away at Garcia’s training mitts as they performed their familiar training ritual in the basement ring.

From time to time, in those days, Garcia would turn to local businessman Steve Tankanow for financial assistance when he wanted to take his pupils to some boxing tournament. At some point along the way, Rivera caught Tankanow’s eye, and he agreed to sponsor the fighter when he turned pro. Over the course of the years, as the young man’s career developed, the trio became “Team Rivera”, making periodic forays into far-flung gymnasiums and auditoriums as “El Gallo” gradually worked his way through the ranks. There were injuries; there were losses; there were agonizingly mistimed illnesses; and there were whole years when they could not find the next rung of the promotional ladder. Like his fighting style itself, Rivera’s career has been an exercise in persistence — persistence that on September 13 paid off, finally, in triumph.

From time to time, in those days, Garcia would turn to local businessman Steve Tankanow for financial assistance when he wanted to take his pupils to some boxing tournament. At some point along the way, Rivera caught Tankanow’s eye, and he agreed to sponsor the fighter when he turned pro. Over the course of the years, as the young man’s career developed, the trio became “Team Rivera”, making periodic forays into far-flung gymnasiums and auditoriums as “El Gallo” gradually worked his way through the ranks. There were injuries; there were losses; there were agonizingly mistimed illnesses; and there were whole years when they could not find the next rung of the promotional ladder. Like his fighting style itself, Rivera’s career has been an exercise in persistence — persistence that on September 13 paid off, finally, in triumph.“I could have gone my whole career without the opportunity for a world championship — that happens to many fighters. I may have not ever gotten the opportunity for this fight. But I was very fortunate, and I hung in there with patience. I worked hard for this.”

El Gallo is 30 years old now, an age when many boxing careers begin to reach the upward reach of their arcs. Divorced in 1998, he takes seriously his responsibilities towards his 10 year old son; he has a young fiancee; he has a respectable job with the Worcester Juvenile Court. He is beginning to look beyond boxing now — to a college degree and whatever life-after-boxing doors that might open. What he still hasn’t had is a major league payday, and the financial boost that can give to his aspirations. With a championship in hand, that day may be coming soon, but each fight and each purse is still a rigorously calculated enterprise for him and his team. The welterweight division is a notoriously tough one, in which the combination of speed and power can conjure up both explosive violence and big money. Rivera understands both the rewards and the risks of this phase of his hard-fashioned career.

El Gallo is 30 years old now, an age when many boxing careers begin to reach the upward reach of their arcs. Divorced in 1998, he takes seriously his responsibilities towards his 10 year old son; he has a young fiancee; he has a respectable job with the Worcester Juvenile Court. He is beginning to look beyond boxing now — to a college degree and whatever life-after-boxing doors that might open. What he still hasn’t had is a major league payday, and the financial boost that can give to his aspirations. With a championship in hand, that day may be coming soon, but each fight and each purse is still a rigorously calculated enterprise for him and his team. The welterweight division is a notoriously tough one, in which the combination of speed and power can conjure up both explosive violence and big money. Rivera understands both the rewards and the risks of this phase of his hard-fashioned career.“I probably feel like I have six fights left in me and then I want to be done,” he says. “I throw it out there — to my family, to my fiancé — and I tell them that if there comes a point where I have had enough, please let me know. I have accomplished one goal; now the next goals are not too far behind. So it shouldn’t take too long, if it happens at all. It shouldn’t take too long to achieve those goals and get myself and my son situated before I shouldn’t have to fight anymore. Then I can go to school and do other things with my life.”

But for the moment — and he is learning to relish it — Rivera is world champion. He is the city of Worcester’s favorite adoptive son and Exhibit A for the notion that one really can make dreams come true — a subject that he addresses directly when he talks — as he does regularly — to local youth.

“I tell the kids that they can be anything they want to be and do anything they want to do,” he says: “As long as they are willing to put the work into it and make the sacrifices they need, it can happen. Now the only difference is some dreams don’t come true and some don’t happen, but along the way, as you’re working for that, many other things happen, many other doors open, many other opportunities or good things happen for you, because you were willing to put in the work for your dreams.

“I don’t feel like I deserved this,” he continues. “I think God has blessed us and he gives us things, even if we don’t deserve them; but you have to earn it, and I feel this I earned. I worked for this — no one gave it to me. I don’t deserve it, but I earned it. “

His supporters, to a one, agree.

Photos: from top to bottom-

1. Jose Rivera displays his trophy-belts from several championship fights.

2. When he’s not boxing, Jose Rivera is a court officer at the Worcester Juvenile Court.

3. Jose hits it hard at his personal gym on Shrewsbury Street.

4. Jose and his two sisters Anna Guzman (l) and Maria Rivera-Ortiz after winning the MA state championship in 1991

5. Jose’s 10 year old son Anthonee, a student at Worcester’s Arts Magnet School

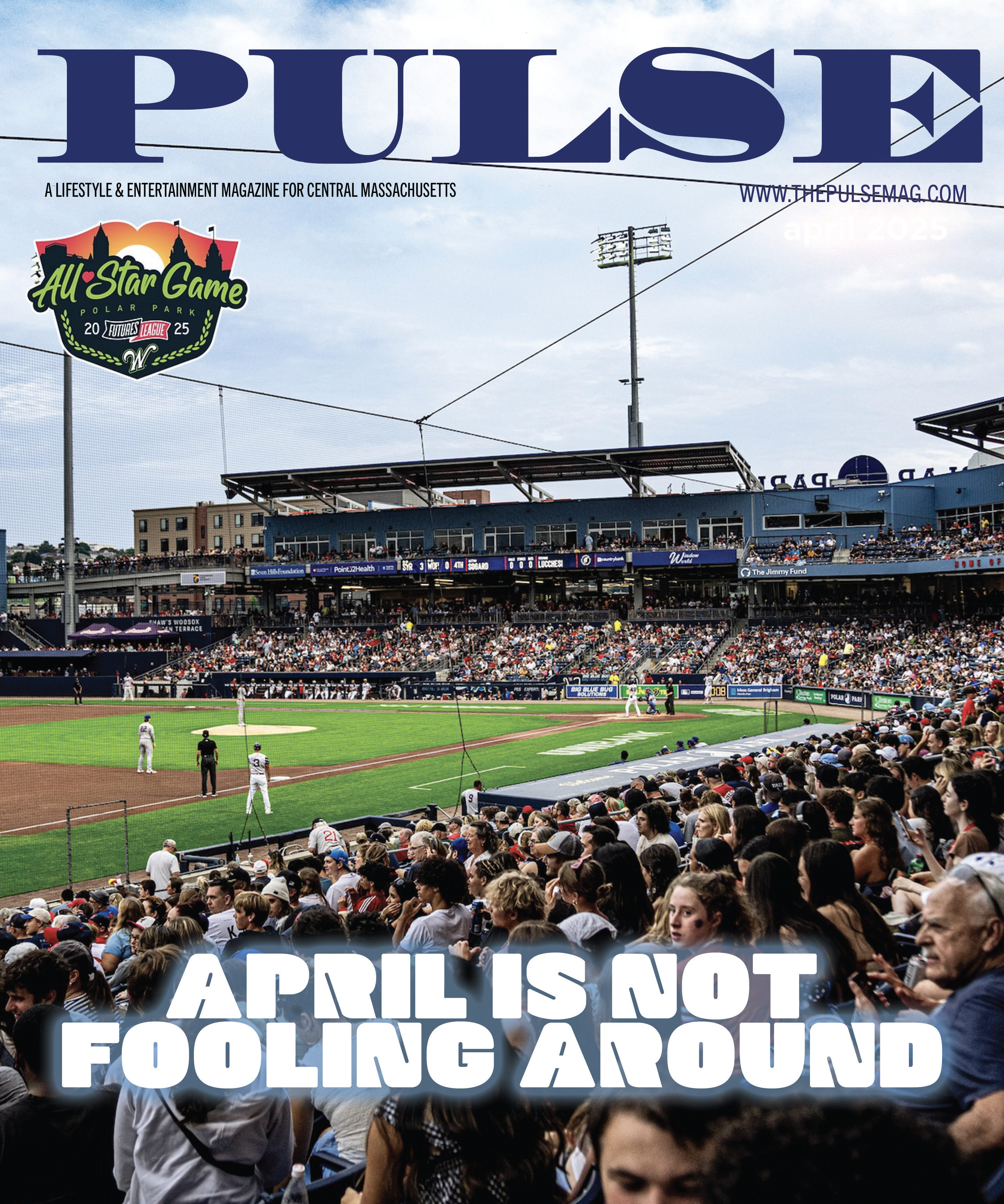

Boxer Jose Rivera talks about his triumph at the recent world welterweight championship in Berlin, Germany

Boxer Jose Rivera talks about his triumph at the recent world welterweight championship in Berlin, Germany

Comments are closed.